If you’ve been paying attention to tech news lately, you’ve probably noticed a pattern. TechCrunch has been going absolutely nuts reporting on fundraising for AI startups that are, in a lot of cases, nothing more than a flashy demo. Every other headline is about some company raising $50M to “revolutionize” something with AI.

It got me thinking: what would the parody version of this look like?

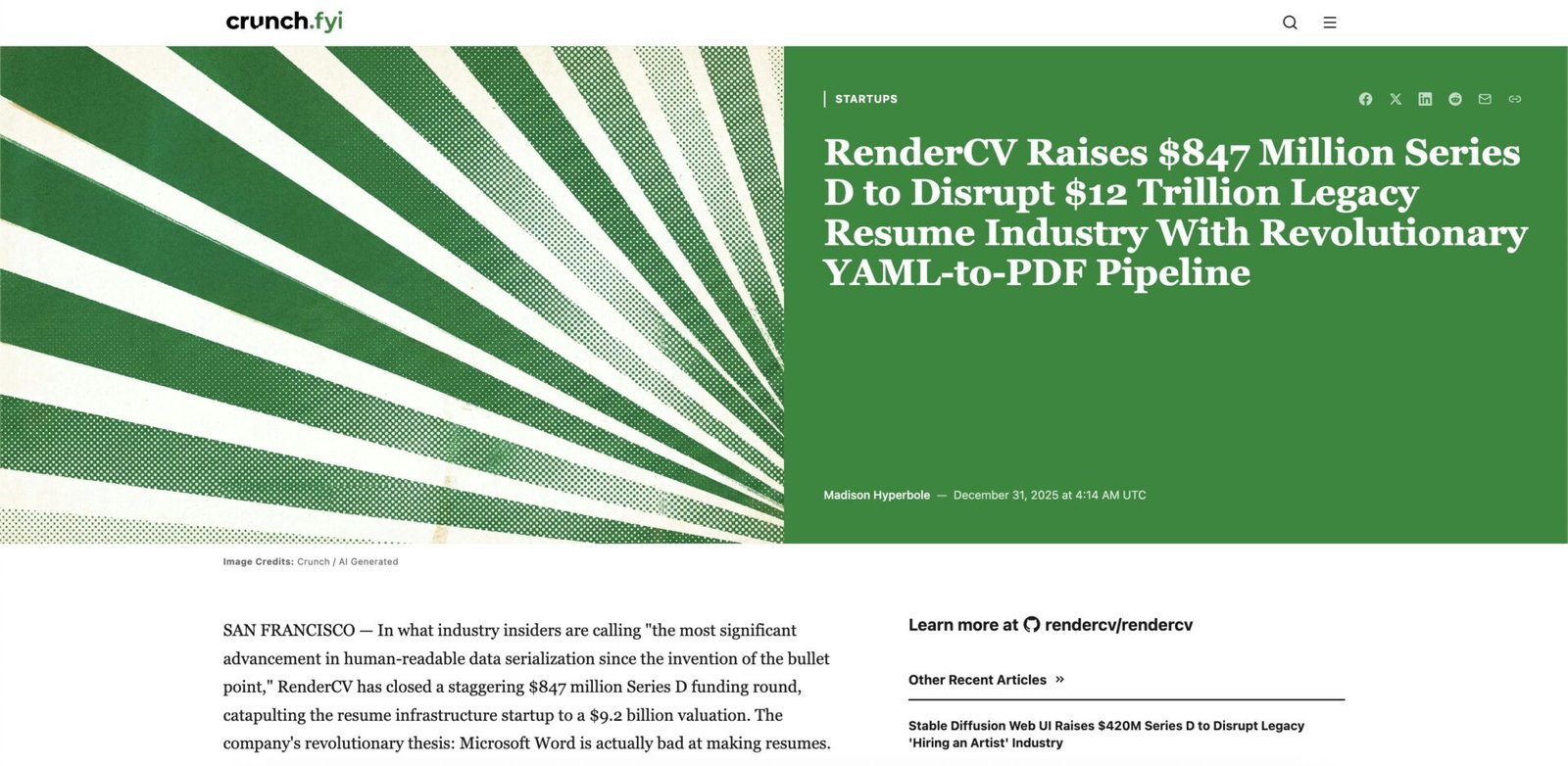

The original idea was simple. Paste any GitHub repo URL, and an AI agent would analyze the project and generate a satirical TechCrunch-style article about how it’s “changing the world” complete with fabricated funding rounds, anonymous VC quotes, and buzzword-laden headlines.

Here’s an example of what it produces:

SAN FRANCISCO — In what industry insiders are calling “the most significant advancement in human-readable data serialization since the invention of the bullet point,” RenderCV has closed a staggering $847 million Series D funding round, catapulting the resume infrastructure startup to a $9.2 billion valuation. The company’s revolutionary thesis: Microsoft Word is actually bad at making resumes.

I decided to turn this into a winter break project to see just how far I could push Claude Code (which runs on Opus 4.5) as a building tool. The deployed system itself uses Sonnet and Haiku—but Claude Code wrote nearly all the code. What I didn’t expect was how much I’d learn about agent architecture along the way.

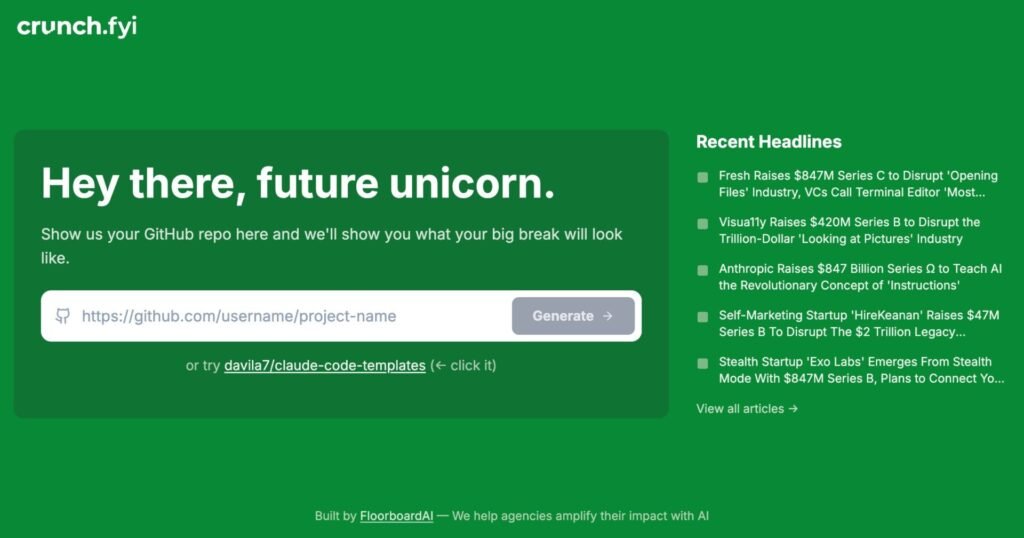

If you just want to see the code and skip the story, here’s the GitHub repo. Or go try it yourself at crunch.fyi.

Our first try: can we just dump everything into the LLM?

My first attempt was the naive one. Grab the contents of the repo we were investigating (README, package.json, maybe guess at some of the key files) and feed it all to Claude in a single prompt. Then, ask it to write a satirical article based on what it sees.

This kind of worked. But I kept running into the same problem: I had to decide what to feed it ahead of time.

That meant I was making choices about what context mattered before the model ever saw the repo. For repos I knew well, that was fine. But for random repos people might paste in, this meant our prompt would sometimes miss things. The model would write an article that completely ignored the most interesting part of the project, simply because I didn’t know to include that file.

The output depended entirely on my pre-selection algorithm, which is a pretty brittle approach when you’re building something meant to handle arbitrary repos.

It got me wondering: what if I could just let the LLM discover what it thought was interesting?

Second approach: enter the Claude Agent SDK

That’s when I started looking at the Claude Agent SDK.

The Agent SDK handles the agentic loop (tool calls, responses, state management) for you. Instead of a single prompt-response, the model can use tools repeatedly until it decides it’s done. This was key for my use case because I didn’t know how many loops I’d need to truly understand a GitHub repo. Some repos are simple, with clear READMEs that have all the context I need. Some have sprawling codebases with hidden gems buried in subdirectories. By letting the agent decide when it had enough context, I didn’t have to be prescriptive about it ahead of time.

So I gave the agent tools to explore repos via the GitHub API. It could list files, read READMEs, check out the package.json, and dig into source files that looked interesting. The agent would poke around until it felt like it understood what the project was about, then write the satirical article.

This worked a lot better. The agent found things I wouldn’t have thought to include. It would notice a weird dependency, or a TODO comment that was comedy gold, or a contributor with an amusing bio.

But there were two problems.

First, it was (relatively) expensive. Everything was running on Claude’s Sonnet model, including all the exploration turns. Every time the agent decided to read another file, that was another round trip with the full context window.

Second, context management got tough. All that exploration noise was polluting the context that the model needed to write creatively. By the time the agent got around to actually writing the article, the context was stuffed with file listings and README fragments and GitHub API responses. Not ideal.

Third approach: subagent architecture

That’s when it clicked. This problem actually fit into another agent architecture pattern: the subagent.

Instead of one agent doing everything, you have a main agent that can delegate to specialized subagents. Each subagent gets its own context, does its job, and returns a result. The main agent never sees the messy details, just the result.

For my use case, this meant splitting the work into two agents:

Repo Scout (using Claude Haiku): Explores the repository via GitHub API. Gathers metadata, reads the README, pokes around the file structure, checks out interesting source files. Returns a clean summary of what the project is about and any interesting tidbits it found.

Writer (Claude Sonnet): Takes the scout’s summary and writes the satirical article. Crafts the clickbait headline, invents the funding round, makes up the anonymous VC quotes.

This solved both problems at once.

Haiku is cheaper and faster than Sonnet, so the exploration phase (which potentially involves lots of turns) costs less. And the writer agent gets a clean context with just the summary, not all the exploration noise. Separation of concerns, basically.

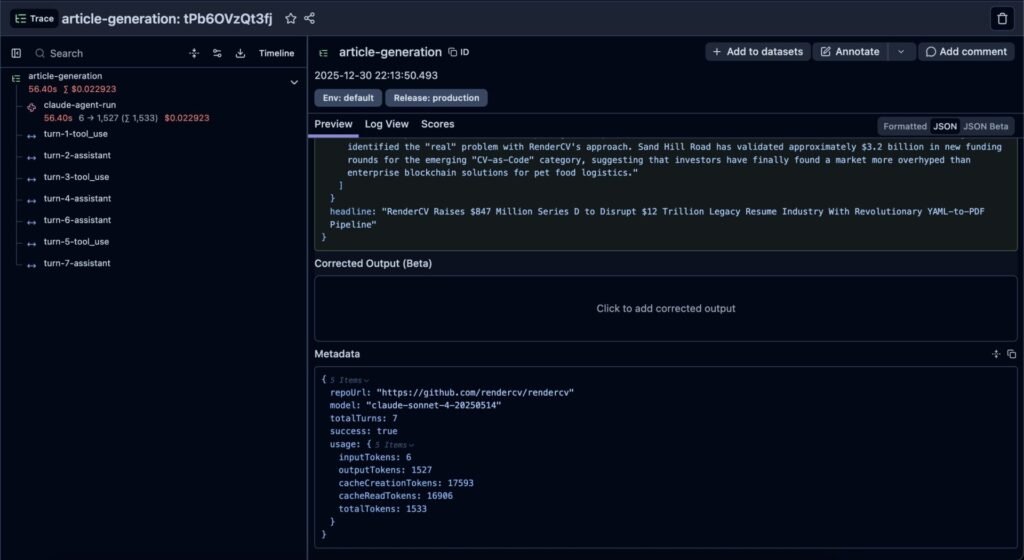

Looking at the before and after in Langfuse (the tool I’m using to keep track of how my agent is working), these improvements are pretty clear.

Before: ~2 minutes to run a full generation, ~$0.03 per article

After: ~45s – 1 minute to run a full generation, ~$0.02 per article

That’s about a 33% cost reduction and 50% time reduction. Not bad for what was essentially an architectural refactor.

There was a bonus realization too: the repo scout subagent is actually useful outside this project. It’s a general-purpose “understand this GitHub repo” tool. I’ve already found myself wanting to reuse it elsewhere.

Refining the output with human feedback

With the architecture working, the next question was: how do I make the articles actually funny?

I could have spent hours tweaking the system prompt myself, trying to anticipate what would work. Instead, I realized that I already had about 20 written articles that derived from the current prompt, so I asked Claude Code to help me iterate.

The process was simple:

- Ask Claude to show me a random paragraph from one of the generated articles

- Give my feedback on what I liked and didn’t like

- Repeat about 20 times with different paragraphs

- Ask Claude to incorporate all the feedback into an updated system prompt

This turned out to be a surprisingly effective way to refine the tone. For example, one paragraph was entirely about how many GitHub stars the repo had, which I said focused too much on vanity metrics. Another paragraph called out specific function names and Tailwind classes, which was way too technical for satire. In both cases, I just said “remove this kind of thing” and Claude incorporated it into the system prompt.

The adjustments were things like: lean more into the absurdist VC-speak, don’t let the satire get too mean-spirited. The kind of stuff that’s hard to specify upfront but easy to recognize when you see it.

There was one other tweak that helped: I told the subagent to not be too technical and only explore as much as necessary to understand the repo.

Originally, it dove deep into what framework the project was using or how specific functions were implemented. This made the article very technical, but also used a lot of agent turns. And in the end, these technical details didn’t make the article better, in my opinion.

Making this change to the prompt cut down on over-exploration and unnecessary technical details in the output, with the benefit of reducing the generation time (and cost) even further.

Takeaways

Building this project taught me a few things about working with Claude Code and Opus 4.5.

The failure mode is usually my prompting, not the model

I kept trying to find things that would break or confuse Opus 4.5. Edge cases, ambiguous requirements, complex multi-step tasks. But I couldn’t really find anything. Every time I thought I’d found a limitation, I realized I just hadn’t explained what I wanted in enough detail.

This was a useful reframe. When something doesn’t work, my first instinct is now to ask: did I actually explain this clearly?

Knowing architecture patterns unlocks a lot

Claude Code becomes much more effective when you can suggest specific patterns. Instead of hoping it figures out that you need job queue persistence, you can say “let’s use Redis.” Instead of waiting for something to break, you can pre-empt it: “does this account for what happens when someone submits a private GitHub repo?”

The more you know about what’s possible in software development and system design in general, the better your collaboration becomes.

Plan mode made bigger features go faster

Before diving into substantial features, I used Claude Code’s plan mode to think through the implementation first. Plan mode helped me think through the worker architecture of the Redis queue, how SSE would communicate progress, and where rate limiting should live.

The framework it uses of asking you questions one at a time is super powerful and is something you can and should specifically ask for, even if you’re not using plan mode.

This all meant the actual build went faster because the path was already clear. And it caught architectural issues before they became expensive to fix.

Try it yourself

If you want to give this a try, go to crunch.fyi, paste your favorite GitHub repo (or choose the suggested one), and watch the satirical article generate in real-time.

And if you want to dive deeper and see how this all works, the full source code is on GitHub.

If you’re thinking about building AI-powered systems like this (whether it’s agent architectures, LLM integrations, or figuring out where AI fits into your product), I do consulting and advisory work to help folks with just that!

Shoot me an email at keanan@floorboardai.com and let’s chat.